Martin Luther is, deservedly, receiving most of the attention as we mark the beginning of the Reformation in Saxony. But with remarkable speed, those teachings spread to other countries in Europe. How did that occur? Largely through the work of some courageous leaders. Let’s look at how the Reformation came to a few countries whose descendants have helped shape the ELCA.

In Sweden, two brothers, Olavus and Laurentius Petri, spearheaded the Reformation. Both had studied theology with Luther in Wittenberg. They returned to Sweden around the same time King Gustav I Vasa was creating an independent nation. He made Olavus pastor of the city church in Stockholm, where he translated the New Testament into Swedish, created a catechism, published an order of worship, and provided a Swedish hymnal. Meanwhile his younger brother, Laurentius, was made the first Lutheran archbishop of Sweden; he and Olavus jointly produced a complete Bible in Swedish.

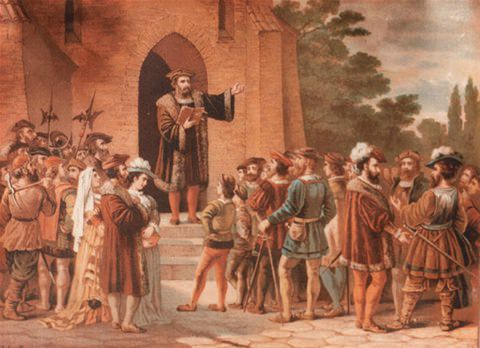

In Denmark, too, the Reformation came early. As in Sweden, it was led by a young man who had studied under Luther in Wittenberg—Hans Tausen. The ruler at the time, Frederick I, was formally opposed to Reformation ideas, but he protected Tausen and tolerated Lutheran writings. The next king, Christian III, stripped the Roman Catholic Church of its wealth, and Luther’s pastor, Johannes Bugenhagen, made a journey from Wittenberg to crown the king and help organize the Danish church.

Norway was, at the time, ruled by Denmark, and initially the spread of the Reformation there was slower. Christian III tried to encourage its growth there, but at first there wasn’t much popular support; it was more of a top- down reformation. Nevertheless, pastors such as Jorgen Eriksson, who would become bishop of Stavanger, preached Lutheran teachings, and the Reformation gradually took hold.

Mikael Agricola was yet another student of Luther, and it was he who led the Reformation in Finland. At that time, Finland was ruled by Sweden. The first Lutheran bishop of Turku (and thus of Finland), Martinus Skytte, left most Roman Catholic orders in place. Agricola’s ministry as the next bishop, though, mirrored much of Luther’s: he translated the New Testament into Finnish, and in the process created the Finnish literary language. He prepared a prayer book in Finnish, created a vernacular order of communion, and collected Finnish hymns. He was also the first married bishop of Turku.

Moving southeast from Wittenberg, Slovakia is another area where the Reformation took hold. Two visionary people must receive much of the credit. Jan Hus lived about a century before Luther and ministered in neighboring Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), but his reforming teachings influenced Slovak Christians, as they did Martin Luther himself. So the way was prepared for the Reformation from Wittenberg. And in the early seventeenth century, another graduate of the University of Wittenberg, Jiřῑ (or Juraj) Třanovský, helped cement the Reformation in Slovakia by translating many hymns and collecting them into a hymnal called Cithara Sanctorum (“Lyre of the Saints”).

Lutherans from these lands and many others came to America, establishing first separate enclaves, but gradually merging with other Lutherans into church bodies, including our current Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.